A heretical view of Sparta

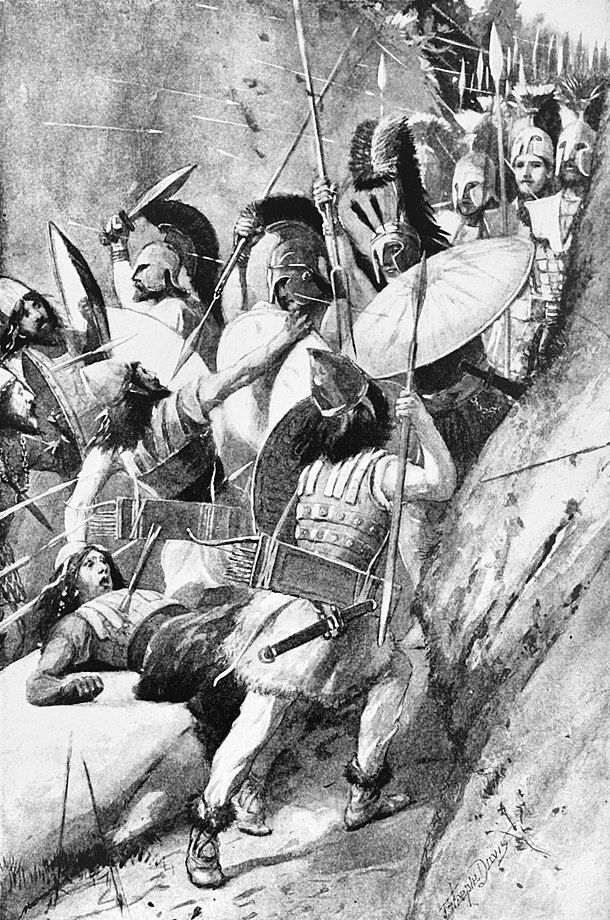

When Ancient Sparta is mentioned, King Leonidas and his sacrifice along with his 300 hoplites at Thermopylae automatically comes to mind. The general perception is that Ancient Sparta was a well governed state, where everyone adhered to strict principles, obeyed the laws and was ashamed to be seen otherwise. Of course, the behavior of its inhabitants is mentioned as a good model for our time. In principle the Spartans themselves do not seem to have left anything written about themselves but all our sources consist of what others wrote about them. So let’s analyze our sources trying to get the real picture of ancient Sparta in the light of science

Plutarch writes during the times of Roman occupation. The Sparta of his time was a tourist attraction for wealthy Romans who went to see its inhabitants reviving Spartan education and the regime of Lycurgus’ laws. (or at least attempting too) The «Great Rhetra» attributed to the legendary king Lycurgus and apparently carved in the sanctuary of the Sylanian deities (Zeus and Athena) was rather used as a manual of historical revival, because we know from Plutarch and Polybius that the Lycurgian constitution had been abolished during the Hellenistic period and the victorious Romans imposed government changes. So Plutarch in the «life of Lycurgus» and the «Laconic Provebs» of his Moralia probably conveys to us an idealized image of Ancient Sparta and not what really happened in the Geometric and Archaic period in Sparta.

Xenophon, who was a close friend of the Spartan king Agesilaus and had been exiled from Athens for being a Spartan sympathiser (laconophilia), ican be questioned for his objectivity. Confined as a foreigner, to Lepreo, according to the fixed Spartan custom of not leting foreigners moving freely in their territory, he describes to us what was told by the authorities of a Sparta, that had been defeated at Leuctra and Mantineia and had lost its Messenian territories. As a result of this it could not maintain the army it once had and hat to live in a state of siege. This meant probably enacting extraordinary legislation that might not have existed in the Archaic or Geometric era.

According to the sources, there were three classes in Sparta. The «homioi», (free citizens with political and military obligations and the right to vote and be elected to public office) the perioikoi (free citizens with military obligations but without political rights) and the helots (enslaved former residents of the area). Based on the above authors we know about the life of the «homioi» and the helots. The women of the «homioi» are considered to have had freedoms that the women of other Greek regions did not have, but the only evidence we have is mainly for the women of Athens and perhaps only for the aristocratic families. The men of Sparta if they passed the elders’ inspections that they were healthy had 53 years of military service ahead of them (from their 7th to their 60th year). Children who were not considered healthy were not killed but abandoned and perhaps some survived in childless families of periokoi or even helots. The «homioi» of course exercised civil rights and governmental authority but were forbidden to engage in anything other than military training and military service. The kings also had the right to veto laws that thought they could eventually harm the interests of the state.

The helots did allthe farm work and heavy labour. They were taxed at 50% of the produce to support the «homioi». They were considered state property but the behavior of their masters was extremely harsh and they were ready to revolt in every opportunity. Let’s not forget that they weren’t slaves imported by being baught and sold, like e.g. in Athens but formerly free people. But Herodotus tells us that at Plataea each Spartan hoplite was followed by 7 helots who were equipped to fight also as light infantry. In other words, the “”homioi tolerated those who would rebel to be…. armed! This contradicts the accounts of Plutarch and Xenophon. Thucydides also says that the Spartans promised freedom to those helots who agreed to enlist and then massacred the 2000 volunteers they accepted in their army. A little difficult to accept this as he tells us at another point that 20,000 slaves of the Athenians defected to the Spartans. It is hard to believe that they would flee to those who would exterminate them without mercy.

We know almost nothing about the periokoi who are thought to be people submitting to invading Doreans without a fight. Herodotus and Thucydides mention them in the composition of the Spartan army. The opinion that only the «homioi» enlisted for military service does not correspond to reality. The production and wide dissemination of Laconian artefacts outside of Sparta in the 6th pre-Christian century, testifies to the existence of artisans and traders and also casts doubt on the strict limitations of Laconian monetary policy. It is a little difficult to accept that the copper imported into Sparta for the manufacture of weapons was paid for with iron coins, the metal of which had been rendered useless by soaking them in vinegar.

Source: Britannica Kids

Another issue is the education of young people (Agoge). Successful completion of this «training material» was a prerequisite to being named a citizen of Sparta. The criteria for entry into the system other than the child’s health and fitness are unclear. Mothakes (born from a mother who did not belong to a «homioi» family) are proof that free people could introduce the children they had with slaves (or even concubines) to Education System, and help them to rise socially. We are not aware of any restrictions for children of the perioikoi. Could this have been an indirect way for the perioikoi to exert political influence in the assembly: (Appella) All boys entering the Agoge until they joined the military at age 18 had 11 years of living away from their families under the supervision of the paedonomoi and older teenagers in a style of everyday life that reminded the «devil weeks» of the modern special forces. We can’t even imagine the psychological pressure they faced. Sparta’s full-time hoplites were superior in survival and non-phalanx combat skills even to the elite hoplites of other Greek cities. Their main occupation, however, was policing the helots. It was therefore more of an elite militarized gendarmerie than a typical army, hence the reluctance of the Spartan authorities for distant campaigns.

And the view that the Spartans went to war out of contempt for life is wrong. Plutarch writes that when someone wanted to sell a rooster for cockfighting (a popular spectacle in Sparta) saying that it was so aggressive that he would be killed in battle, the Spartan replied: «better to kill the opponent!». The governors also punished a young man who rushed naked into battle against rebel Helots because, if he were killed he would deprive Sparta of a valuable soldier.

Even for the battle of Thermopylae, which is considered the epitome of Spartan military virtue, if we combine the information of Herodotus and Diodorus we will see that it was a raid against Xerxes that failed and not a heroic rear guard battle. After all, Herodotus also writes that he was informed about the facts by the ephors of Sparta, perhaps in the light of political expediency.

In conclusion, ancient Sparta was an admirable society that can teach us much more through rational scientific approach than through idealization.

Sources

Plutarch «Lykourgus» Loeb Classical Library ed.1920

Plutarch «Moralis» Loeb Classical Library ed.1920

Herodotus «Histories» Loeb Classical Library ed.1914

Xenophon «Hellenica» Classical Library ed.1914

Xenophon «Spartan constitution» Classical Library ed.1914

Xenophon «Αγησίλαος» Classical Library ed.1914

Diodorus Siculcuc «Histories» Loeb Classical Library ed.1914

Thucidides «Histories» Loeb Classical Library ed.1914

https://www.spartareconsidered.com/

hollow-lakedaimon.blogspot.com